Broadcast Package

Hear the voices of the players in the college admissions process.

One student worked at his uncle’s taco truck. One student did not speak for a year after his brother was shot and his father committed suicide. One student caught the eye of the Sunglass Hut security guard’s hand reaching for a stun gun as he entered the store.

College essay coach Louise Tutelian hears stories like these from the low-income high school students with whom she volunteers through Minds Matter of Los Angeles, an organization that helps underprivileged students apply to college.

“The stories these students were telling me were so compelling,” Tutelian said. “Hearing them tell them like they were no big deal...that was addicting to me.”

Outside of Minds Matter, the former New York Times journalist also offers private college essay help in Santa Monica. Compared to these wealthier clients, the students Tutelian coaches while volunteering tell very different stories.

“They’re used to doing things for themselves,” Tutelian said about her Minds Matter students. “They don’t have the snowplow effect, things being pushed out of the way for them.”

“Snowplow effect” or “snowplow parenting” describes parents who will lie, cheat, bribe, or anything else to clear the path for their children’s success and to avoid any chance of them experiencing rejection.

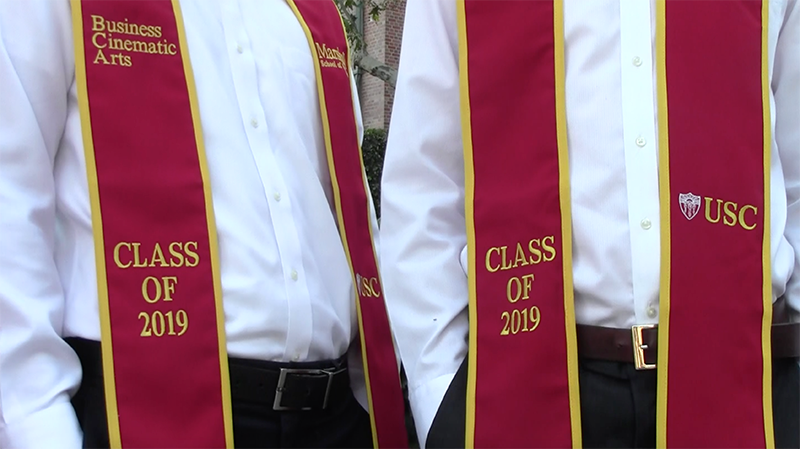

This terminology has grown in popularity since the college admissions scandal broke last March. Parents, private counselors, and others were accused of bribery that influenced undergraduate admissions at universities like Stanford and the University of Southern California, using methods like forging standardized tests or pretending to be student athletes to get accepted.

The scandal’s revelation indicates the importance placed on attending highly-acclaimed universities and the lengths people will go to get there. This college admission obsession impacts all players involved: parents, students, teachers, counselors, and tutors experience the pressure and costs of applying. On May 1, this year’s applicants decided which universities they will attend after enduring the admission journey.

Hear the voices of the players in the college admissions process.

The “snowplow effect” Tutelian referenced exemplifies the parents’ side of the obsession.

“If you can think it, there’s a parent who can do it,” Tutelian said.

Parents like Jacqi Callaghan, a mother of an alumnus and a current junior at Santa Monica High School, or SaMoHi, have not taken their college preparation to the same level as those prosecuted. Callaghan said she feels the pressure to buy help.

“I don’t blame the people that did it. I blame the system and how it can be done,” Callaghan said.

Australian-born and unfamiliar with the American college process, Callaghan paid for SAT tutoring and application help for her older son.

“There was very much a culture around me that it was do or die,” Callaghan said. “What college you get into, and the steps you take to get to that point, was everything for your child.”

Claudia Bautista, a Spanish teacher at SaMoHi, said that the “do or die” mentality is reflected in the students’ work ethic.

“They’re working so much harder than we ever did in our generation, and they’re still not getting in,” Bautista said, noting that the lowering of acceptance rates is a systemic issue.

This academic pressure to succeed affects SaMoHi students daily, according to Owen Halpert, a junior at the school.

“The conversation on this campus is just like, I need to get an A on this test, I need to keep my A in this grade, I need to be a valedictorian candidate,” Halpert said.

Part of this pressure includes attending a four-year university, regardless of cost.

“There are so many kids from this school who would rather go to some random school in the middle of the country than take a year at [Santa Monica College] just because of its reputation as being a community college,” Halpert said.

Student at SaMoHi

Teacher at SaMoHi

Parent of Student at SaMoHi

Education Director at 310 Tutors in Santa Monica

Founder of College Zoom

Four-year universities have varying acceptance rates, which community colleges inherently lack. Colleges tend to advertise when they lower acceptance rates to showcase prestige. This also makes universities desirable for students. If accepted, applicants can cite the statistic with pride: they are students worthy of taking a spot. Attending community college does not carry this honor, which might pressure lower-income students to ignore a potentially financially safer option for a recognizable university name, well-suited for resumes when competing in the job market.

College counselors at local high schools recognize the competitive drive within the college application process. Even Santa Monica’s private Crossroads School, which markets itself as college preparatory and sends its students to top universities, shares with its students that acceptance rates are not everything.

“We work hard to help families avoid the pitfall of associating a college's selectivity with its quality,” said Arthur McCann, the dean of college counseling at Crossroads. According to McCann, Crossroads stresses fit over acceptance rate.

As an application-based private high school with an annual tuition, Crossroads practices its own variation of selectivity. But, the school does not favor high socioeconomic statuses. Crossroads has 47% of students identifying as people of color — similar to SaMoHi, with just over 50% — and over $9 million allocated to financial aid per year to a quarter of its students. When expressing concerns about the college admissions industry, McCann mentioned testing fees, which impacts lower-income Crossroad students.

“Colleges should host the standardized exams that they require and/or the exams should be web-based, scored instantly and the scores should be shareable with colleges for free.”

The compounding fees associated with applying to college can become a financial burden on applicants and their families.

“I’ve seen what I think is, unfortunately, a huge scam, and something that is geared towards the wealthy,” Callaghan said. “To pay college counselors, to pay for AP exams, to pay for SAT, ACT exams, you need to have money. And, even if you don’t, you feel like you want to go into debt.”

Bautista said she is concerned about the intentions behind charging such fees.

“It is now becoming a business rather than an ability to educate our kids and people that will be productive in the future,” Bautista said regarding the journey to attending higher education.

According to Tutelian, the industry is out of control, starting to market to potential college applicants as early as middle school. Despite scandals or business plans, she said that college acceptance will come for the students who lawfully fight for their chance for education, regardless of socioeconomic background.

Though she works with families who spend extra money on college preparation, Tutelian also sees the lower-income students, the underdogs who cannot pay extra, who have studied hard and earned their seat in the lecture hall.

“The ability to work as hard as necessary is unlike anything I’ve ever seen.”